Humidity: Poor Man's Altitude?

The simple reason for this common trope is that both force your body to operate in a state with less oxygen—therefore increasing the strain on your body.

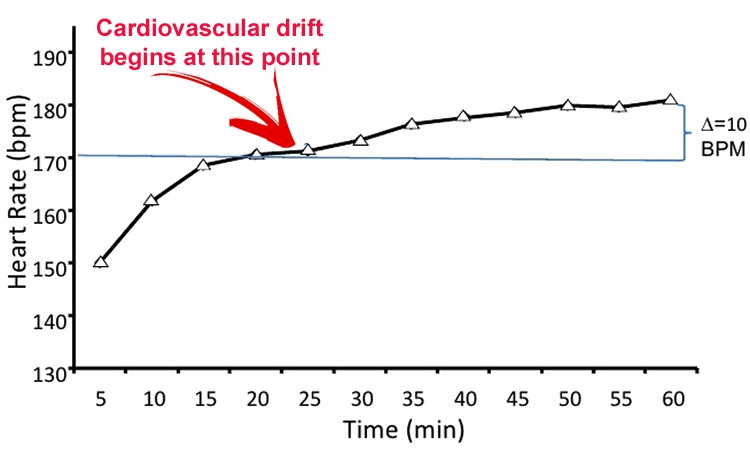

With altitude, you are oxygen deprived from the start due to there being less oxygen available to inhale around you. When it comes to humidity, it is a slow burn, and is actually affecting your cardiac drift more than anything. If your cardiac drift usually occurs within an hour of running in normal conditions, you can generally count on halving that time (therefore causing an earlier added strain on your body).

Cardiac Drift = The progressive increase in heart rate to meet the demands of your output. As you become dehydrated, there is less plasma in your blood and your stroke volume drops. To counteract this, your body increases BPM.

Sweating in dry conditions is the ideal environment for humans to operate. We heat ourselves up due to activity, which increases our core and skin temperate, so we sweat. We “water” our bodies, then the dry air evaporates the sweat, causing a cooling effect. (Dry + windy is actually the best way to stay cool! When sweating in these conditions, it can actually feel much cooler than the temperature reads.)

During times of high humidity, the opposite happens—as in nothing happens. The sweat you produce has no where to go, therefor you are not cooling/regulating yourself. This is because there is already water vapor in the air, so not evaporation on your skin occurs. Causing the sweat on your skin to become trapped and actually act a thermal layer, HEATING you up—not fun.

If your sweat isn’t evaporating, then your skin temperature heats up, which causes your body to divert more resources to your muscles (aka oxygen). This in turn heats your core temperature up as well.

All of this means you have a higher strain (BPM) on your body at paces you normally would not.

Unlike with humidity, we see athletes actively seek out higher altitudes throughout the year for specific training. The adaptations come rather quickly as well—a month is all that is needed to become well adapted. There is plenty of science backing the year-round training in higher altitudes correlated with sea-level racing. Anecdotally, you just have to look at the best American runners training in Colorado, Utah, Arizona (Flagstaff), California (Big Bear), etc. to name a few. Or more famously, the Kenyan Kalenjin tribe living at 8,000ft elevation producing world record Marathon holders.

But this begs the question: can humans adapt to humidity (from a training perspective), and are there advantages to be had?

Or simply put: Can running in a humid area, and racing in a dry environment forge faster results?

The answer is similar to a lot you get in the fitness space…Yes and No.

Training in humid conditions can significantly benefit all runners, particularly when training for a race that will be in a drier climate. Simply put, running in humidity stresses the body, leading to increased cardiovascular efficiency, improved thermoregulation (sweat a crap ton more), and enhanced mental resilience. These adaptations can make runners more efficient at managing heat/humidity and improve overall performance *for when* the weather is more favorable.

And if nothing else, there is a major psychological benefit to heat/humidity training, anything “normal” becomes very easy. Do not underestimate this power!

The key point in there is that your body adapts to heat/humidity by sweating *a lot* more than you normally would. Especially with humidity. When humidity is high, above 70%, you can easily become soaked in heat that, if it were dry, you would not overly-notice your sweating.

This is where the problems occur. You become dehydrated at a rate you are not used to in training. Cardiac drift occurs much earlier due to this dehydration (and increased plasma), sending your heart rate through the roof. To *help* (not fix) combat this, electrolytes should be consumed before your run, salt with every meal, and bring water with you on your run. Water + electrolyte intake must go up two-fold.

In terms of RPE in the summer heat/humidity, I am a fan of only correcting your heart rate by 5-10BPMs. So if your normal pace has you at 135BPM, allow that pace to be 140-145BPM in heat/humidity. If someone tells you to “throw heart rate out the window in summer months”, please ignore any/all advice from that individual.

I cannot stress the importance of not pushing too hard during humid runs to avoid overuse injuries and hormonal stress. This is the #1 killer of runners. Pushing yourself too hard to become fit, and letting your hormones take a hit. Running too hard and too often in the heat *will* do this.

This is why RPE must be thrown out the window. I always suggest a balanced approach for my clients:

One RPE session a week (usually weekend)

Run to HR, allow for 5-10BPM increase off of your normal cool weather pace/effort.

Run strides with ALL of your runs. (Keep power output high since you will be running slower)

1-2 sessions a week running intervals—from stride pace to top end speed. Again focusing on power output.

Hydrate during every run outdoors.

Try my training plans: